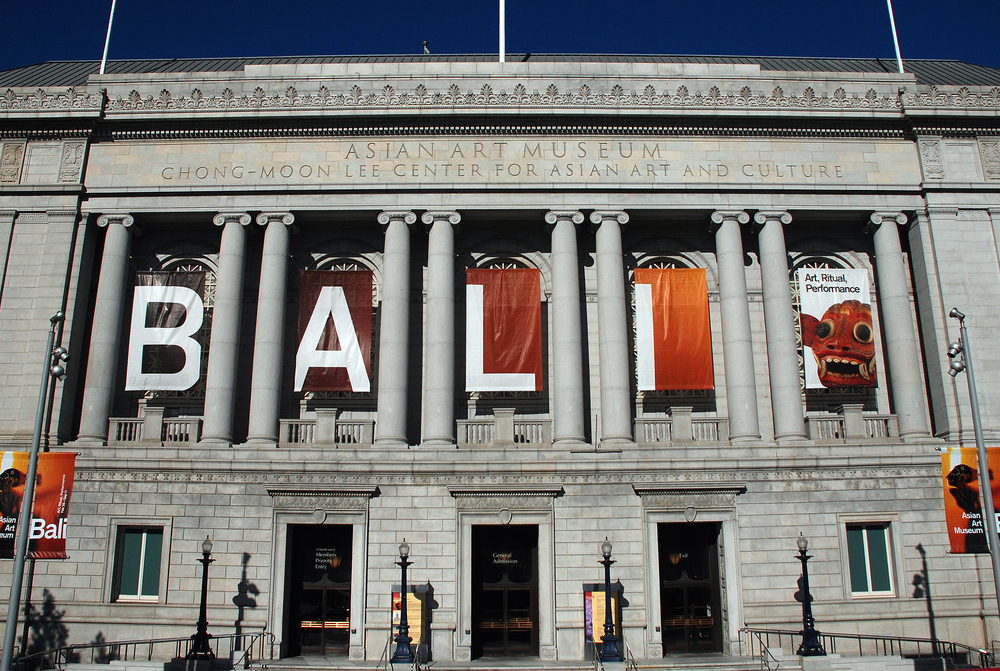

Black Swan Event: Why Did a Tech Billionaire Defy the Odds and Give Big to a Museum?

/photo: Sarunyu L/shutterstock

The "black swan theory" is a metaphor that "describes an event that comes as a surprise, has a major effect, and is often inappropriately rationalized after the fact with the benefit of hindsight." Black swan events include the sinking of the Titanic, World War I and the election of Donald Trump.

I'd like to add another example to this list: a massive gift from a Silicon Valley billionaire to an arts organization.

By giving $25 million toward a $90-million "transformation project" of the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, Yahoo! co-founder Jerry Yang and his wife, Akiko Yamazaki, suggest our understanding of the rules of probability, logic, and arts philanthropy may be structurally flawed.

After all, tech funders, ever beholden to the "ROI mindset," simply don't give to the arts. Or so goes the stereotype. What's more, the Asian Art Museum currently carries $90 million in debt; conventional wisdom suggests donors—tech or otherwise—should be leery of costly capital projects, which always seem to run over-budget and cause massive headaches.

Add it all up and Yang and Yamazaki's gift warrants a closer look.

Where are the Tech Patrons?

"Tech funders don't give to the arts" is a sweeping statement, but relatively speaking, it's a pretty accurate one.

From an anecdotal perspective, start by checking out IP's Visual Arts vertical. The number of profiled gifts over the past seven months coming from tech donors? Zero.

Or do a search on "arts" IP's (admittedly non-exhaustive) list of prominent tech funders. You'll get a modest number of hits, but a closer look reveals two things. First, tech funders' support of the arts is usually secondary to more measurable causes like the sciences, education and health, like the Gates Foundation's Art of Saving a Life Initiative. And two, you won't find many major tech donors like Zuckerberg, Brin, Ellis, et al.

One outlier is Paul Allen, but even his visual arts-related gives came with caveats. He generously funded the establishment of the Experience Music Project/Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame, but that was over 10 years ago. And his Seattle-based gallery, Pivot Art + Culture, opened in December of 2015, only to close less than two years later.

Other outliers include Qualcomm co-founder Irwin Jacobs, a major benefactor to the San Diego Symphony Orchestra, and David Bohnett, who's supported the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Los Angeles County Museum of Art at substantial levels.

Still, the overall generalization holds: Techies aren't big givers for the arts. In describing Yang's gift, the New York Times' Jori Finkel called it "a rare example of high-level cultural philanthropy from Silicon Valley’s entrepreneurial elite."

The reason why this elite tend to sit on the sidelines when it comes to funding the arts aren't a mystery.

"A Difficult Field to Measure Impact"

Winners from tech tend to have backgrounds in science, emerging from the worlds of software development and engineering to score big with new companies. Or they've come into tech on the business side. Either way, these are people who tend to be the most excited about innovation and problem solving, and are drawn to data and metrics. It's not surprising that the ideas of effective altruism, where the primary success metric is "lives saved per dollar," have made a big impact on the world of Silicon Valley philanthropy. Or that funding the opera would be low on the list of tech givers' priorities.

Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes hit on this point a couple of years ago:

If a donor gives money to a new center for the study of a particular topic at their alma mater, then how are you going to look into data to quantify that impact? Or if you start talking about the arts, that’s a difficult field to measure impact.

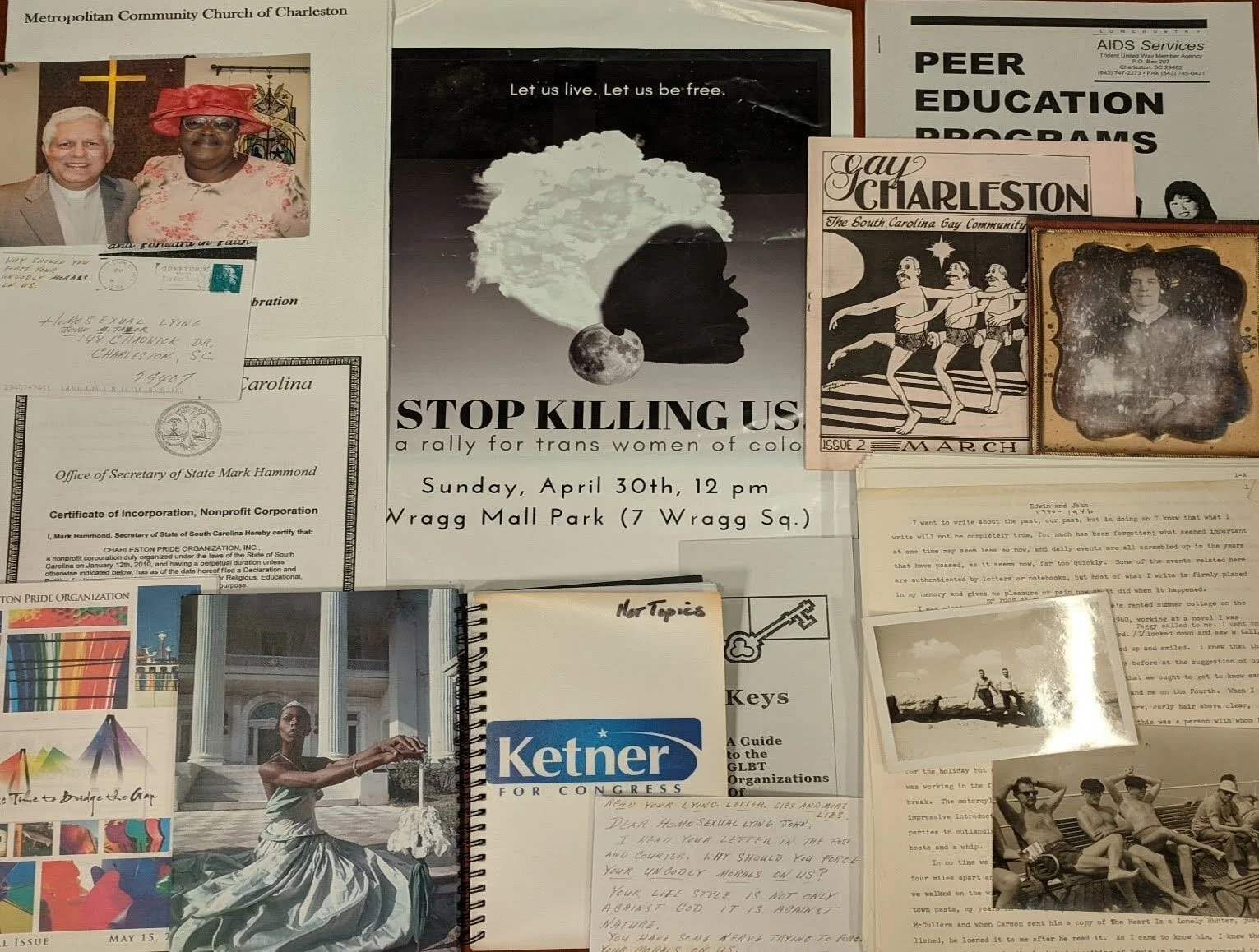

He was right then, and he's right now. Arts organizations have come a long way in their ability to measure impact, but not far enough to get techies to open their wallets on a larger scale. This challenge, unsurprisingly, is especially pronounced in the Bay Area, where tech donors' lack of support has frustrated arts proponents mightily.

For instance, last year, the Silicon Valley Ballet ran out of money, compelling attorney David Lindsay Barch to declare that "the stinginess of corporate philanthropy in Silicon Valley is a disgrace to the region and its residents. Even the robber barons of old did more for the arts and culture of their time than the penurious gorgons that reign today."

Yang and Yamazaki bucked conventional wisdom, and that's the good news for arts organizations. So what are some takeaways, here?

Tech Philanthropists: Beyond the Stereotypes

One lesson of this gift is that tech philanthropy isn't just orchestrated by the male tech entrepreneurs who've (almost always) made the money. It's also partly—or even largely—directed by their spouses, who often have a broader worldview. Sure enough, Akiko Yamazaki is a key to understanding this gift. She is an equestrian and co-founder of the Wildlife Conservation Network. And she also serves as chair of the Asian Art Museum. She was elected to that position after growing more involved in the museum's governance, including 15 years as a trustee at the Asian Art Museum Foundation, the museum's private fundraising arm.

Yamazaki and Yang are also collectors. Yang traces his interest in calligraphy to his childhood in Taipei, Taiwan, when he would take his calligraphy kit on the bus to class to learn the traditional art form. Back in 2012, he assembled a selection of Chinese calligraphy at the Asian Art Museum, and was quick to call attention to his unique situation. "What’s a tech guy doing with brush and ink—arguably the lowest form of tech possible?" he asked in the exhibition's catalog.

His collection subsequently traveled to the Met in 2014. How many "tech collectors" take their collections to the Met? (That was a rhetorical question, by the way.)

Yang and Yamazaki also have a history of arts-related giving, having donated more than $2 million to the San Francisco Ballet. This explains his gift to the Asian Art Museum: Very rarely do we see a donor drop $25 million without some history, however small, of related arts giving. (Though there are the occasional outliers.)

Philanthropists Keep Evolving

Few philanthropists are static; their giving is nearly always a work in progress, and can evolve dramatically over time.

Jerry Yang may be a good example of this. He is still relatively young (48) and has plenty of wealth (around $2.5 billion). It can take a while for many business leaders to get around to large-scale giving, but once they do, the gifts can really start to flow.

Up until now, Yang and Yamazaki's philanthropy mainly consisted of a few large grants to educational institutions, primarily his alma mater, Stanford, or, as previously noted, smaller grants to a handful of arts organizations. Yang and Yamazaki's $25 million gift to the Asian Art Museum suggests that the couple may be ready to step up their giving a notch.

But the $64,000 question is this: Will other tech donors follow Yang and Yamazaki's lead and channel their inner black swans to give big for the arts?

Don't bet your Bitcoins on it.