“Inclusiveness and Openness of Spirit.” A Donor Makes the Case for Free Museum Admission

/4kclips/shutterstock

In 2017, William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust Assistant Executive Dorian Burton succinctly articulated the prevailing donor sentiment across the arts philanthropy space. “Philanthropic efforts in the arts,” he said, “must make a fundamental shift from charitable gifts that exclude to justice-oriented giving that creates equitable access for all.”

Few arts funders disagree with his assessment. But the devil, as always, is in the details. How can organizations create equitable access for all? Burton’s Kenan Trust launched a $6 million program to promote art that advances social justice at some of New York’s most elite “legacy” institutions. Donors have also given millions to support the inclusive programming at organizations like The Shed, the new the cultural center on Manhattan’s Far West Side.

In Los Angeles, meanwhile, a donor is turning to what may be the simplest equalizing strategy of them all: Make museum admission free.

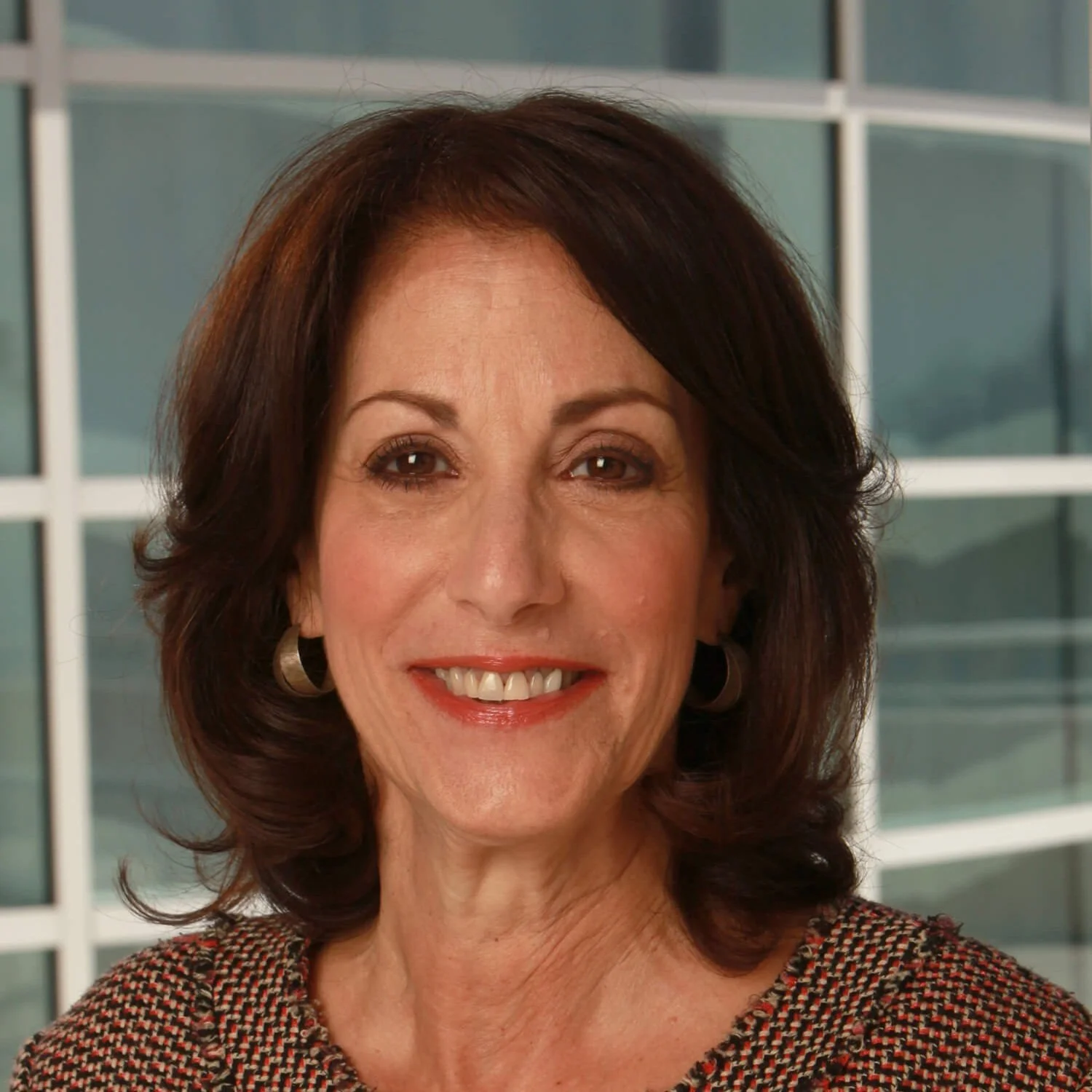

At the Museum of Contemporary Art’s (MOCA) recent gala dinner, Board of Trustees President Carolyn Powers announced a $10 million gift that will enable the museum to offer free admission. The new policy aligns with the MOCA’s “civic-minded” vision of removing financial barriers and making the museum more accessible, said director Klaus Biesenbach. Currently, MOCA general admission for adults has been $8 to $15. The museum is free on Thursday evenings.

MOCA says it is working on a “roll-out plan to implement [Powers’s] gift as soon as possible,” telling Hyperallergic, “The gift gives us five years to create new fiscal strategies and develop revenue streams to support free admission. We have every intention that this is a permanent shift for MOCA.”

The catch? Research suggests that free admission may not boost attendance. No matter, Biesenbach told Los Angeles Times’ Deborah Vankin. “We are not aiming at having more visitors or larger attendance, but we’re aiming at being more accessible, at having open doors. As a civic institution, we should be like a library, where you can just walk in.”

While museums are under pressure to increase attendance in order to boost revenues and also ensure donor support, Biesenbach’s vision, reinforced by Powers’ gift, suggests that in a climate where museums seek to ensure “equitable access for all,” the goal of inclusiveness can trump number-crunching.

“You Have a Civic Responsibility”

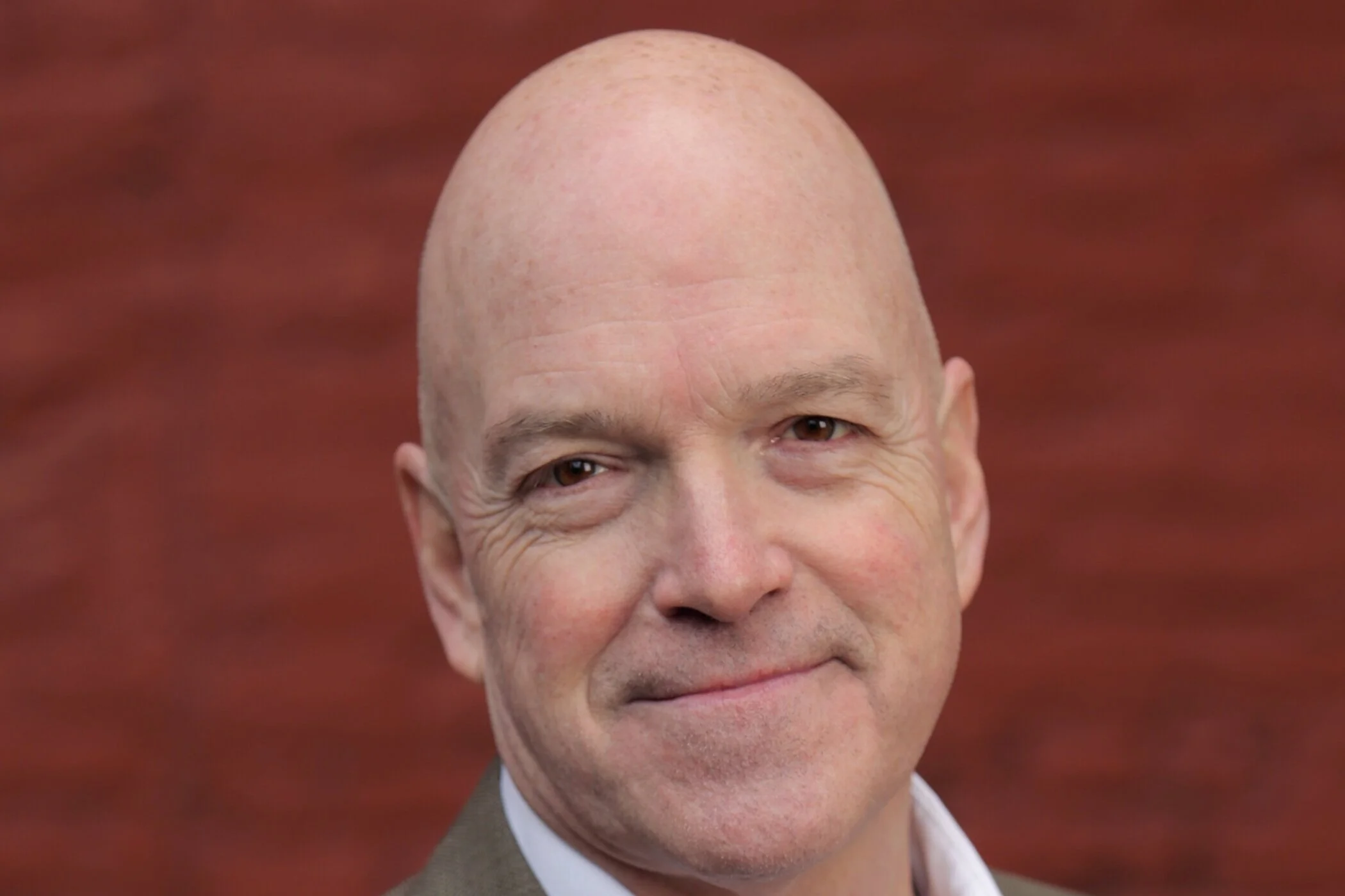

Biesenbach, who assumed leadership duties last October, inherited a museum wracked by leadership changes, internal drama and financial challenges. In November of last year, he sat down with the Times’ Vankin to lay out his vision moving forward.

His priorities included diversifying the MOCA’s collection and exhibition programming to better reflect L.A.’s diversity, especially its Asian and Chicano communities, beefing up curatorial staff, growing attendance, and focusing on fundraising.

A museum, Biesenbach told Vankin, is meant not only to display art, but to support artists and greater civic life by hosting voter registration initiatives or expanding educational programming. “As a museum, you have a civic responsibility, you have a role in society, you have to be courageous, you have to open up your doors to allow for dialogue,” he said.

Biesenbach’s comments may sound familiar. As often noted, museum stakeholders and the donors who support them increasingly view museums, to quote Madeleine Grynsztejn, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, as “active spaces.”

“Audiences today want a space where they can come together and interact,” she said. “We are finding that people are really hungry for civil and civic dialogue—now, more than ever.”

Biesenbach told Vankin he was considering free admission, although the math was rather daunting. “Unfortunately,” he said at the time, “it would cost the museum about $2 million a year to not take admission.” Powers’ $10 million gift has made that a moot point for the next five years.

There are other business-related dynamics to keep in mind, as well. The MOCA isn’t located in Topeka. Rather, it’s in a city that, according to critics, has too many museums. The Broad, which is located across the street from MOCA, as well as Westwood’s Hammer Museum, also have free admission. So while this competitive dimension didn’t factor into Powers’ public statements, MOCA’s new policy nonetheless puts it on a level playing field with the city’s other free museums.

A Broader Inquiry into “Accessibility”

While MOCA is concerned about the bottom line, one of the key takeaways from Biesenbach’s chat with Vankin is the idea that “accessibility” goes beyond financial considerations. For instance, one of Biesenbach’s other big priorities is to make the Geffen Contemporary more physically accessible by adding better signage and a new, Metro-adjacent entrance.

But more than anything, he and Powers speak of accessibility as if it’s something akin to a transcendent Platonic ideal. To see how this ideal can be distorted by equally ephemeral factors like optics, politics and class, consider The Shed, 3,000 miles to the east.

The Shed, which is on track to meet its fundraising goal of over a half-billion dollars, opened earlier this year. Critical opinion thus far has been mixed. This, of course, can be expected. Critics will always find reasons to pan a museum’s curatorial, programming or design decisions. But more alarmingly, some critics can’t seem to extricate the Shed experience from its local and social context.

The Shed is certainly physically accessible. Its entrance is located close to the 34th Street–Hudson Yards subway entrance. Nor is it outlandishly expensive. Many programs cost $10. What’s more, these programs aim to attract previously untapped demographics—The Shed reserves 10 percent of tickets for residents who live in low-income neighborhoods.

But there are two problems, here. First is the fact that The Shed isn’t located in the outskirts of Detroit, much less, say, outer Queens. It’s situated in Hudson Yards, the city’s new ultra-upscale, Dubai-like neighborhood. With a few exceptions, architecture critics have gleefully eviscerated the district. New York magazine’s Justin Davidson calls it a “billionaire’s fantasy city” where he felt “like an alien.” The Times’ Michael Kimmelman compared it to “some gated community in Singapore.” And Jezebel’s Megan Reynolds called its new luxury mall a “terrifying labyrinth.”

The neighborhood vibe, at least thus far, is far from “accessible.”

As such, according to the New York Times’ Gina Bellafante, The Shed’s very existence can’t be disentangled from its immediate surroundings or its billionaire-funded backstory. “The Shed,” she wrote, “is ultimately an act of repentance for the sins that surround it—an attempt at making amends for all the greed and ostentation embodied in the $23 billion playpen in which it has been sunk.”

Tiana Reid picks up on this theme in The Nation, writing, “Philanthropists, billionaires and companies spout the language of accessibility, diversity, and, most toothless of all, change. They talk the talk while actively making people’s lives worse through egregious labor practices, investments in mass incarceration, and a more general money-hoarding mentality.”

In other words, whatever the inclusive aspirations The Shed might have, it’s entering the New York cultural scene with some serious baggage as a plutocrat-financed institution in a real estate development that strikes many as a symbol of New York’s ever-deepening class divide. Because it’s surrounded by multi-million-dollar condos and towering office buildings, a certain segment of the population is unlikely to feel at home at The Shed, underscoring yet again the truism that “accessibility” is more than just admission fees.

This cultural venue, of course, is still in its infancy. Its opening weekend drew positive reviews and huge crowds. In time, The Shed may successfully engage visitors from poor neighborhoods and, to quote the Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott, “retain some kind of democratic sensibility.”

“Charging Admission is Counterintuitive”

So what will be the ultimate upshot of MOCA’s new bid to become a more accessible institution, courtesy of Carolyn Powers’s generous gift? It’s too early to say.

Research is lukewarm on the correlation between free admission and higher attendance. The Dallas Museum of Art eliminated its $10 admission fee, yet still charged for special admissions. It saw its annual attendance jump from 668,000 to 498,000, including a 29 percent increase in minority visitors. Conversely, the Metropolitan Museum of Art recently implemented a controversial new paid-admission policy. And guess what? Attendance has skyrocketed.

A 2015 study by nonprofit market researcher Colleen Dilenschneider found that admission cost wasn’t as significant a barrier to museum attendance as lack of time and interest. In addition, when free admission did spark higher visitor numbers, Dilenschneider found that it was thanks to people who had returned for a second or third visit—as opposed to newcomers lured in by free admission. “We need to reevaluate our strategy for engaging new audiences because the ‘free admission’ fix may not prove sustainable,” she wrote. “Moreover, focusing on free general admission may be distracting organizations from cultivating more effective engagement strategies and programs for reaching new audiences.”

This research hasn’t stopped donors from supporting free admission. The Bronx Museum of the Arts began offering a free admission program in 2013 that continues today, thanks to support from Shelley and Donald Rubin. Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, which has free admission, has been a huge hit—although it’s not clear if its popularity is due to larger factors—starting with strong public demand. As Walton herself has said, “I knew this museum was needed. I grew up here, and didn’t have access to art, and I knew we wanted to change that. What I underestimated was how much people wanted to have access to that great art.”

Likewise, it’s hard to isolate the role of free admission in fueling The Broad’s enormous popularity. A spokesman for the Eli and Edythe Broad called the couple’s support for free admission at their namesake museum a “gift to the people of Los Angeles. They felt strongly that free admission was the best way to make great works of contemporary art accessible to all.”

And therein lies a key takeaway from the free admission movement. Donors don’t seem to care that there isn’t a strong correlation between free admission and attendance. They certainly aren’t publicly linking their donations to the measurable goal of getting more people through the door. Instead, they’re more concerned with the spirit and optics of supporting an accessible experience, especially if the policy attracts certain demographics that, to quote Michelle Obama, “look at places like museums and concert halls and other cultural centers, and they think to themselves, well, that’s not a place for me, for someone who looks like me, for someone who comes from my neighborhood.”

Carolyn Powers agrees. “This is not a badge for me,” Powers said in a statement released by the MOCA. “Rather, it’s a way for me to support the museum and be of service to the Los Angeles community.” Powers described “diversity, inclusiveness and openness of spirit” as values integral at MOCA and stated that “[c]harging admission is counterintuitive to art’s ability and purpose to connect, inspire, and heal people.”