A Moral and Practical Imperative: A Women's Foundation Fights Mass Incarceration

/Photo: kittirat roekburi/Shutterstock

The U.S. has the highest prison population rate in the world, with 716 out of every 100,000 people incarcerated. For years, philanthropic groups have been addressing mass incarceration, including the imprisonment of youth. But more recently, a growing number of funders have begun to focus on a demographic that was once only a small minority of the incarcerated population: women. Unfortunately, it’s an increasingly urgent topic.

Of the roughly 2.3 million people in our prisons and jails, most are people of color and most are men. But, women are now the fastest-growing segment of incarcerated populations. And, the imprisonment rate for African-American women is twice that of white women. When women, especially mothers, are put behind bars, the negative impacts ripple out to families and communities.

This trend makes the Justice Fund—a seven-year grantmaking and philanthropic mobilization effort recently announced by the New York Women’s Foundation (NYWF)—a timely endeavor. It aims to address mass incarceration and its effects on women, families, girls, and transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) communities in New York City (foundation President and CEO Ana Oliveira often stresses that the foundation includes members of TGNC communities when it speaks generally about women).

“The Justice Fund will focus on systemic reform and investing in alternatives to incarceration that promote fairness, safety, and overall well-being and that build on community solutions and leadership,” Oliveira told Inside Philanthropy.

The fund’s work will involve community-based and cross-sector approaches that “include the voices and visions of individuals with histories of criminal justice involvement,” along with members of locally-rooted organizations and leaders from communities, academia, and research. Early NYWF Justice Fund partners include the Frances Lear Foundation and the Ford Foundation. In a panel discussion, Oliveira described the fund this way: “It is an open fund and we’re going to be inviting everyone else to join us and constitute a source of funding that is multiyear. Changes in justice are long-term changes.”

The Ford Foundation has been backing criminal justice reform for years, partnering with other funders to support initiatives like prison college programs, criminal justice research initiatives, and art-based advocacy projects. A growing number of philanthropies and nonprofits have also turned their attention to mass incarceration in recent years—and the bail system in particular, which leads to hundreds of thousands of people imprisoned daily due to lack of funds. These individuals often take plea deals even when innocent in order to escape this situation. Many women who can’t afford bail are mothers or have other caregiving responsibilities. Efforts underway to alleviate the pains of the bail bond system and bring it to an end include local community bail funds; Appolition, a phone app that lets anyone help pay bails; and the Bail Project, run by former Bronx public defender Robin Steinberg.

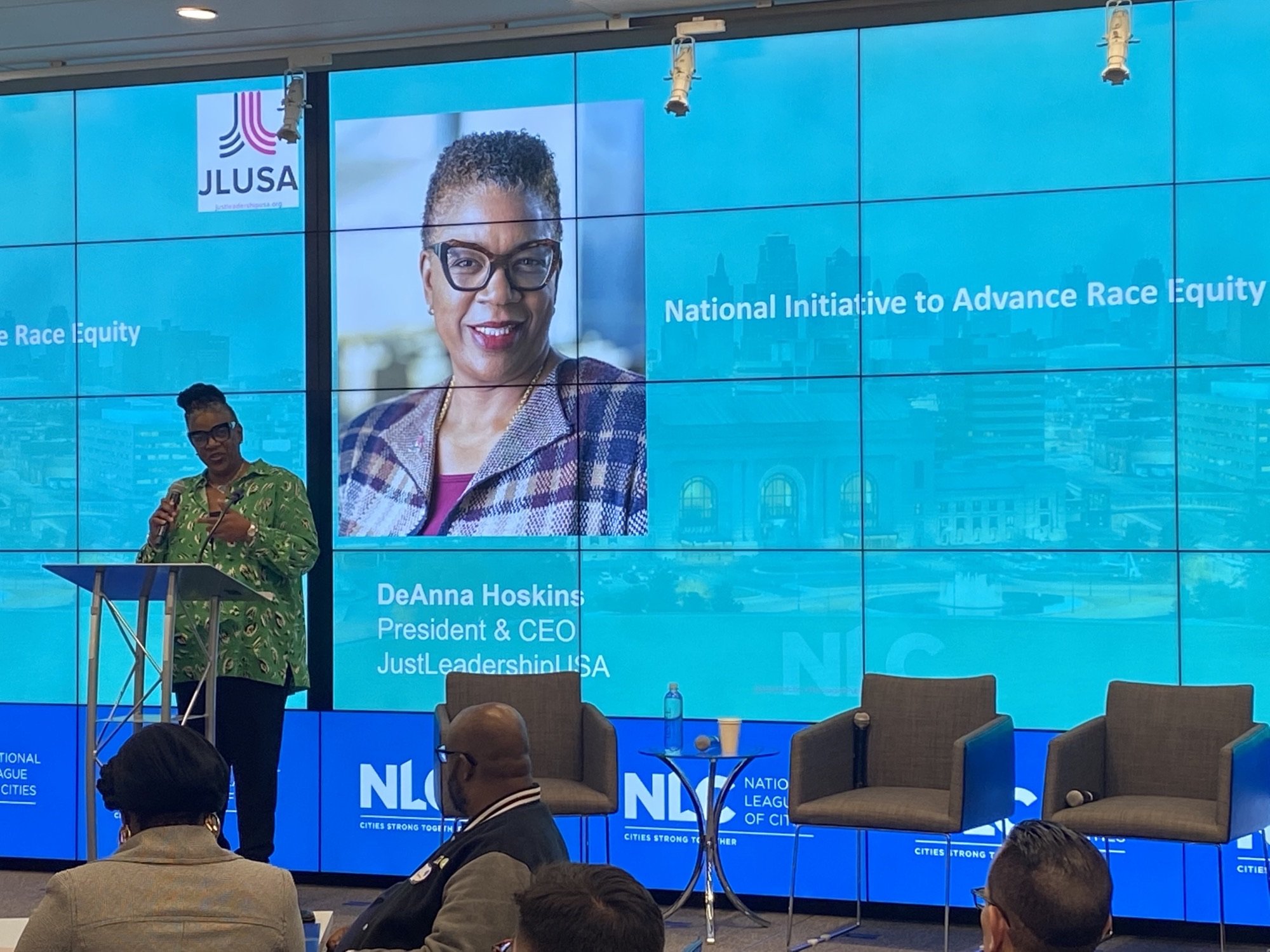

Funders and collaborations focusing specifically on women in jails and prisons include the Fund for Nonviolence, the Rosenberg Foundation, the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation, and the Sills Family Foundation, which is a funder of JustLeadershipUSA, a membership organization of formerly incarcerated individuals that is also backed by Ford and others.

The new Justice Fund partners plan to carry out grantmaking, philanthropic mobilization, thought leadership, and outreach, and to partner with policymakers and city and state-level leaders. Among their goals are reform efforts such as grassroots organizing advocating the closure of the Rikers Island jail complex; bail reform; “capacity building for the ecosystem of local community organizations engaging in reform efforts;” investment in locally-based solutions in areas like housing, mental health services, and leadership development; and education and training for families.

Women’s incarceration affects entire communities.

Oliveira told Inside Philanthropy that closing Rikers, where “conditions are inhumane,” is “a moral and practical imperative.” She said the foundation wants to begin by closing Rose M. Singer women’s jail on Rikers, where many women end up because they cannot pay bail. She adds:

Far too many women are sent there when they could—and should—be diverted to services within the community…. Most are there for very short periods of time; about two-thirds are out within two weeks. Yet, the damage caused by what is most often a senseless interruption in their lives upends their families and communities in ways that don’t happen when men are arrested, because women are usually primary caregivers and are often breadwinners, too. Even two weeks is enough to upset the precarious balance of employment, housing, and child care for some.

Nearly 80 percent of women in jail are mothers, a statistic that exemplifies the NYWF’s point that women’s incarceration affects entire communities. Said Oliveira:

That horrifying statistic is the outcome of socioeconomic and health conditions that women who are marginalized often face; poverty, domestic abuse, substance use, mental health issues, and homelessness. It reflects a lack of consideration by our criminal justice system for what the jailing of a mother does to a family, as well as a lack of alternatives to incarceration.

Furthermore, according to the Urban Institute nonprofit research organization, women—particularly women of color—also suffer when men are imprisoned, due to resulting economic and caretaking strains.

Related:

Disrupting Bail: An Innovative Criminal Justice Reform Idea Gains Momentum—And Funders

Who’s Helping the Formerly Incarcerated Lead the Fight for Criminal Justice Reform?

How One Foundation is Working to Influence California’s Criminal Justice System

State and local policies have driven the mass incarceration of women.

State prison populations have dropped overall since they peaked in 2009, but most of the decrease has been among men. The number of women incarcerated for breaking state and local laws has risen sharply since the late 1970s, but the federal prison population hasn’t changed as dramatically. According to the Prison Policy Initiative research and advocacy nonprofit, this shows that “state and local policies have driven the mass incarceration of women.”

While state-level trends vary, this initiative has identified several likely reasons more women are now in this situation. For starters, women receive more disciplinary action than men when incarcerated, and fewer diversion and rehabilitation programs have been developed for them. Some state criminalization practices target women in an unbalanced manner, the nonprofit finds. Examples are mandatory or “dual” arrests for women fighting back against domestic assault, the persecution of female youth survival efforts such as running away, and the criminalization of women supporting themselves through sex work.

The war on drugs, launched by President Nixon in the 1970s and which the Trump Administration is working to reinvigorate, also has a strong effect on women’s imprisonment. Women are convicted of nonviolent, drug-related crimes more than any other offense. And there’s a lack of research on women's incarceration.

Women and mothers have unique medical needs when incarcerated. Incarcerated women’s rights to safe, shackle-free childbirth, menstruation-related products, and free calls to children would all be protected under the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act, introduced in 2017 by Democratic Senators Cory Booker and Elizabeth Warren. It was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary last summer.

As Oliveira noted, many women in prison have mental health problems and a history of abuse, as do many of the men. The authors of a 2009 National Institutes of Health study report:

Both men and women in prison have histories of interpersonal violence. Extant estimates suggest that at least half of incarcerated women have experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetime… Rates reported by men are lower by comparison but significant nonetheless.

The inequitable bail system, along with the way poverty negatively affects people’s medical and psychological health, leads reformers like Helena Huang, project director for the Art for Justice Fund, to conclude too many people are going to jail who "don't belong there."

The NYWF sees this new funding initiative as one that can benefit everyone experiencing or affected by incarceration. “While the focus will be on efforts targeted toward women, girls, and TGNC individuals,” states NYWF, “it will also recognize that ending the effects of mass incarceration for them means ending mass incarceration for all.”