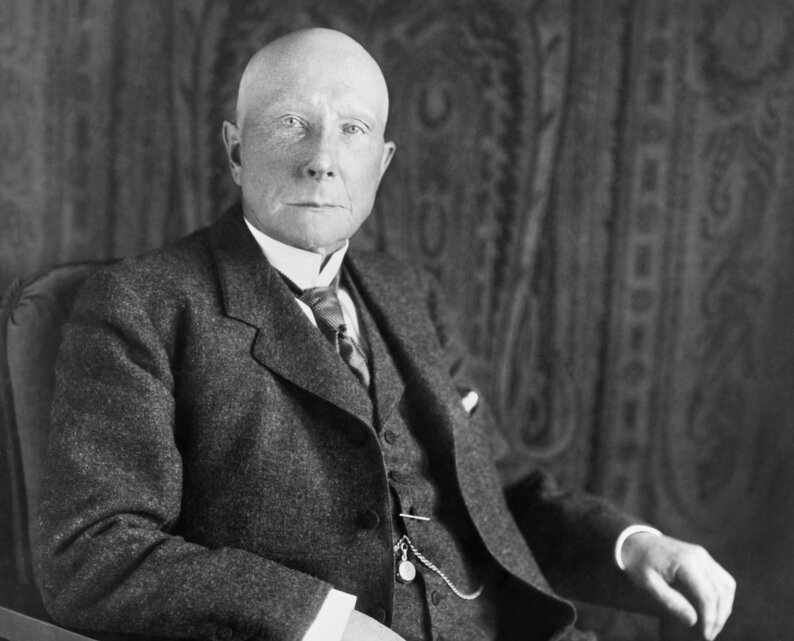

Founding Funder: How John D. Rockefeller’s Legacy Still Shapes Philanthropy

/Everett Historical/shutterstock

It’s hard to be a billionaire these days. Antagonists of the New Gilded Age have set their sights on breaking up giant tech companies that spawn fortunes, raising taxes on the uber-wealthy and curbing the power of “the 1 percent.” As if that weren’t enough, billionaires who step into the world of major giving face criticism about how much they give, to whom, with what expectations.

It’s a good moment to look back at John D. Rockefeller Sr., the original “Big Philanthropist,” who established patterns and practices that have endured for more than a century. Like today’s 1 percent, he was criticized and castigated because of his wealth and power. Like many contemporary billionaires, he made the decision to use a lot of his money to address social issues and problems.

What do modern major donors and philanthropy experts think about Rockefeller’s influence? How do they view his legacy? Did his philanthropic enterprise teach us anything about how contemporary donors should do their work, or have they decided that they should do otherwise? IP asked a number of leaders in the sector to compare and contrast 2020 philanthropic protocols with JDR’s extensive and pathbreaking giving.

The Motivation to Give

Where did JDR’s impulse to philanthropy come from? Some say it was his attempt to whitewash his profile as a ruthless businessman. Rockefeller himself said, "Many folks believe I’ve done much harm in the world, but on the other hand, I’ve tried to do what good I could.”

A more generous interpretation sees Rockefeller’s giving as grounded in “the long tradition of what I've called Christian stewardship,” says Benjamin Soskis, a research associate at the Urban Institute and co-editor of HistPhil, a website devoted to the history of the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors.

Rockefeller “had a sense of responsibility because of great wealth to attend to a kind of charitable giving,” Soskis says. “Rockefeller was an exemplar, but he wasn’t different necessarily from other folks that have come before him. He was extremely engaged in charity from a very early age.”

Rockefeller “had a big impact on me and my children,” says Hilary Pennington, executive vice president of the Ford Foundation. “I read somewhere that when he gave an allowance to his children, he made them put a third of it away for savings, a third for giving, and a third they could spend.”

Contemporary billionaire philanthropists have often pointed to a deeply felt charitable impulse, along with an obligation to give. The late Jon Huntsman Sr. said: “It has been clear to me since my earliest childhood memories that my reason for being was to help others.” Paul Allen said: “I believe that those fortunate to achieve great wealth should put it to work for the good of humanity.” Steve Case and his wife Jean say, “We share the view that those to whom much is given, much is expected. We realize we have been given a unique platform and opportunity, and we are committed to doing the best we can with it.”

So what sets Rockefeller apart? Soskis argues “the most important thing about Rockefeller… is how much money he had.” The original fortune was certainly staggering. He became a titan who managed to control, by himself, 2% of the entire American economy. Calculated in today’s dollars, about $350 billion, his oil-fueled wealth would come close to matching Bezos, Gates, Buffett and Zuckerberg combined.

Mechanisms for Giving

Because JDR was so visible and so rich, he was hammered every week with thousands of requests for donations (one estimate says it rose to 50,000 letters a month). Legend had him opening and reading every letter. The volume of solicitations finally wore him down, even as his fortune kept growing—a problem that will be familiar to today’s billionaire philanthropists, who get richer even as they increase their giving. In 1906, Rockefeller’s philanthropic adviser Frederick Gates wrote to him, “Your fortune is rolling up, rolling up like an avalanche! You must keep up with it! You must distribute it faster than it grows!”

Together, Gates and Rockefeller devised a corporate structure to handle the “asks.” The plan was to move out of the “retail” business of charity and establish a “wholesale” mechanism to give away JDR’s fortune.

Their 1910 proposal to launch a federally chartered “general purpose foundation” was met with significant suspicion and resistance. Antipathy was fueled by Ida Tarbell’s book about Standard Oil, the source of the wealth. Skeptics voiced concerns about large-scale giving by the super-rich that are similar to today’s critiques of “Big Philanthropy.” One critic, Reverend John Haynes Holmes, wrote that “it seems to me that this foundation, the very character, must be repugnant to the whole idea of a democratic society.” Gates and Rockefeller pulled back from their attempt until 1913, when New York State granted the charter.

John D. Rockefeller didn’t entirely abandon his direct personal charity; he carried a bag of new dimes with him to give to people he met, particularly children. In today’s dollars, not a big deal, but in 1920s money, the shiny coins were more than a token.

The Rockefeller Foundation wasn’t the first endowed grantmaking entity, but it was unprecedented in scale and scope. It became the template for large, multi-issue organized philanthropy—with lasting influence to this day. Council on Foundations CEO Kathleen Enright says that the emergence of professionally staffed foundations was a major departure from an earlier model of giving that was more direct and hands-on—an approach that many wealthy people still aren’t comfortable with.

“You’re not the actors,” she observes, speaking of the donors who turn grantmaking decisions over to foundation staff. “You’re not the ones doing the work. That’s actually a hard thing for some donors, because they’re so used to the personal agency of being the doer. That’s how they made their money. A real transition needs to happen.”

On this criterion, contemporary mega-philanthropists straddle both worlds. Some have built robust organizations to make grants; others are primarily doing their giving as individuals. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has eight offices around the world, a cadre of officers and directors, and a staff that numbers close to 2,000 people. By contrast, Phil Knight—certainly Oregon’s biggest donor and arguably the least transparent—makes major gifts that are an expression of his personal interests, mostly unencumbered by boards or staff hierarchies.

Ben Soskis underscores that contrast. “Rockefeller's model was the main model for the 20th century, creating large philanthropic institutions. Today, I think there’s probably more energy toward the kind of ‘giving while living’ model in which living donors take very active roles in their philanthropy and have staff, but there's not as much delegation. And the donors are the real animating force behind a lot of the work.”

Longevity vs. Immediacy

Soskis has put his finger on one of the principal differences between JDR’s philanthropy and some of today’s leading mega-donors. Rockefeller wanted to build a durable mechanism for giving that would go on for years and chip away at complex problems. He wanted his philanthropy to transmit his family’s traditional and religious values. And he wanted the work to be a “family business” for generations to come.

He got what he wanted: His son, John D. Jr., or “Junior” as he was widely known, was the Rockefeller Foundation’s first president; Junior’s five sons created the Rockefeller Brothers Fund; there’s also the Rockefeller Family Fund, a well as foundations managed by individual family members and a capillary system of Rockefeller descendants who support dozens of nonprofits.

This kind of institutionalized giving over decades is “a page that modern philanthropy could take out of John D. Rockefeller's playbook,” Enright believes. She says that today’s nonprofits are wrestling with huge challenges that can’t be solved quickly. They “need flexible, reliable, long-term money to plan for and build the capacity to go deep, to be in it for the long term.”

At the same time, though, a growing number of donors feel a strong urgency to deploy their wealth quickly to have greater impact. Many philanthropists are embracing time-limited giving and creating “spend-down” foundations. They want to make a dramatic impact on tough problems in their lifetimes. And they believe the way to do that is to concentrate giving on one or two issues and go all-in. This trend has recently been documented in a report by Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, a family-founded nonprofit that acts as a fiscal sponsor and counselor for major donors.

Given the scale of his fortune, Rockefeller didn’t have to choose between spending big today or preserving wealth over time. He could and did do both, rapidly deploying vast sums to attack big problems and build new institutions, while also leaving behind a huge endowed foundation. For many of today’s lesser billionaires, though, there’s an unavoidable trade-off between acting with greater urgency or locking away capital for the future. Interestingly, JDR offers a model for either path: He showed how to throw lots of money at a challenge, while the multiple Rockefeller institutions that exist today offer a case study in how philanthropic capital can exert influence over generations—and even centuries.

Whatever choices today’s philanthropists make, it’s key that they appreciate all the giving that’s come before them, says Kathleen Enright. “My preference would be that the new mega-donors come online and build from all of the bricks of knowledge that have been laid by the more traditional foundations, the foundations that have been around a bit longer—really creative, smart foundations, like the Ford Foundation or Rockefeller or the Packard foundation, Hewlett, others that have have learned a lot over the course of their tenures.”

Getting Strategic

Visible or opaque, corporate or individualistic, the sheer weight of kinetic and potential philanthropic capital is massive, dwarfing what even John D. Rockefeller might have imagined. So it’s not surprising that in addition to how mega-donors give, there’s a lot of discussion about what they give to.

“The vast wealth that’s coming online will punch below its weight unless it starts to take on some root causes and the things that drive inequality,” says Pennington. Her view (shared by many) is that mega-philanthropy has an opportunity and an obligation to tackle some of society’s most difficult challenges.

Here, too, John D. Rockefeller’s approach to giving, and the impact he demonstrated, have had a profound influence. When he shifted his primary attention from direct charitable giving to a more structured, corporate model, “he came to the conclusion that what was really necessary was to move to philanthropy that focused on trying to address root causes” says Stephen Heintz, president of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund.

“One of the important elements of JDR’s legacy is the search for cures as opposed to the amelioration of symptoms. That’s still practiced by a lot of philanthropy today, although there are different emphases among foundations. There’s a lot of diversity and a lot of variation, but there’s a real focus on this strategic or solution-focused philanthropy.”

Beyond an appetite for getting at the roots of problems, contemporary billionaire donors might do more to dig even deeper and make systemic change, Pennington says. “I think a lot of times when philanthropy has done its best, patient work over time—think of apartheid in South Africa or marriage equality here—it helped change people’s sense of what's OK and what's not OK. And when you get those kinds of changes, they tend to be much more durable. I don't see as much curiosity or innovation [among new donors] about rules of the game, power dynamics, belief systems as one would wish.”

Rockefeller’s two greatest priorities as a philanthropist were health and education. Today, these twin concerns also drive the giving of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the only grantmaker whose resources come close to matching Rockefeller’s. Gates focuses heavily on huge investments in research to improve global health abroad while giving heavily to boost education outcomes in the U.S. Likewise, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative—another philanthropy powered by one of today’s largest fortunes—is committed to “eradicating disease and improving learning experiences for kids.”

In other ways, though, Rockefeller wouldn’t easily recognize today’s Big Philanthropy. While JDR set out to create sustainable institutions and public programs that would endure, modern mega-donors are often out to disrupt the system, shake things up, stir the pot.

“Oftentimes, new major foundations that come online want to blow up the model. They want to do everything completely differently,” Enright observes. Where JDR sought the counsel of advisors from established disciplines and traditions, some of today’s big donors go their own way. Pennington says, “In our own experience as we try to put together new collaborations and partnerships, very often, the newly wealthy billionaires opt out. They say, 'Oh, I love what you're doing. I'm doing my own thing.’”

Perhaps most striking is the eagerness of many mega-donors to influence or partner with government—a sector that’s dramatically larger than it was in Rockefeller’s day. Philanthropists like Michael Bloomberg, Charles Koch and Tom Steyer pour huge resources into shaping public policy on issues like guns and climate change. Meanwhile, a growing number of grantmakers are teaming up with government in public-private partnerships to tackle major problems like housing affordability and urban poverty. Some of JDR’s philanthropy also involved working with government, such as his campaign to eradicate hookworm, but these collaborations were limited—reflecting the much smaller size of public institutions in the early 20th century.

The Social Context

JDR made his considerable fortune in the fossil fuels business. He was so successful that he controlled 90 percent of the country’s oil industry. There were dozens of complaints about Rockefeller’s labor practices and antitrust actions that broke up Standard Oil. He and Junior were vilified by much of the press.

But there was no protesting the extraction and refining of oil. The nation and the world wanted it, environmental activism hadn’t happened yet, and the criticism was about how JDR did business, not what business he was in.

Times have certainly changed. A case in point: the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and Rockefeller Family Fund have both divested their holdings in fossil fuel companies.

RBF’s Stephen Heintz remembers “starting that conversation with the board in early 2014 and moved pretty energetically to debate it. And it was because half of our board are members of the Rockefeller family, it was a very big decision for them. They are completely committed to the fight against climate change, but it was a very big, emotional and values decision for them. But they ultimately embraced it over the period of the first three quarters of that year, and authorized me to make the announcement in September that the RBF had decided we were going to divest from fossil fuels.”

How would Rockefeller feel about divestiture? Heinz says, “If he were alive today, John D. Rockefeller would be in the forefront of investing in the clean energy economy of the future because he would see, as the visionary that he was, that that’s where the world was going to get, and he would want to get there first… he decided there was a future moving away from whale oil and he was going to lead it. And today, he’d be saying, ‘You know what, there’s definitely a future away from petroleum, and I want to be in the forefront.’"

Finally, consider society’s antipathy toward great wealth—it was as unpopular in the early 20th century as it is in 2020. How did JDR handle the criticism, and what impact did it have on his philanthropy? How should today’s donors respond?

It’s said that Rockefeller mostly ignored the attacks, telling his Standard Oil colleagues to “let the world wag.” His response seemed initially to backfire because the government broke up Standard Oil under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act; he got the last laugh because all of the pieces after the breakup (which he owned or controlled) went on to make even more money.

Certainly, JDR didn’t let the attacks on his wealth interfere with his philanthropy. He was methodical and deliberate about his philanthropy (much as he was in business). He increased his charitable activity after the breakup, launching the Rockefeller Foundation three years after the antitrust action.

The tension between his business record and his philanthropic energy may have lessons for today.

Ben Soskis thinks so. “Many of the major donors today are operating in an environment which is hostile to many of their philanthropic acts. Rockefeller, unlike, say, Carnegie, was a very reluctant public figure. He didn’t see giving as something that had to be done in public. And his advisors had to basically convince him that having as much money as he had necessarily made him a public figure. Philanthropy in the modern age would have to be public.”

The Council on Foundations’ Enright sees some upsides in the criticism of big donors: “It’s provoked some thinking very deeply about how philanthropy can do more and better and be more transparent… there are some foundations that are not paying any attention, clearly, but most rooms that I am in, foundation leaders are being really thoughtful, and caring about what they’re hearing.”

“There is obviously an anti-democratic feature in the DNA of philanthropy,” Stephen Heinz says. “It is the result of massive economic inequality. We need to own that and recognize it and change our practices as a result of that reality.”

“We really have a responsibility—given that anti-democratic DNA—to operate in a way that is as transparent and open as possible. We are not democratic institutions, so we need to adopt certain democratic practices around accountability and transparency to demonstrate that we are, in fact, doing our best to put the wealth to good use on behalf of the common good.”

Ford’s Hilary Pennington signs on, too: “We really hear that rumble, and we think it’s justified, and we don’t think it’s going to go away... you cannot have the kind of pervasive inequality we have in our politics, in our governments, in our economy, without asking those kinds of questions. What’s disappointing is that one would wish that philanthropy would be a first-mover to self-regulate. Why are we not being the ones to stand for paying adequate taxes? Why are we not saying yes, we need a conversation about a more inclusive kind of capitalism? I think right now, philanthropy is pretty much back on its heels, and it’s disappointing that it is not being more proactive.”

Coda

If John D. Rockefeller is something like the Woody Guthrie of philanthropy, all the others since are “Woody’s children.” His decision to use his massive fortune for the good of society, and the ways he chose to formalize and institutionalize giving, clearly resonate through the decades.

So, too, does the very fact of discomfort with great wealth. There is work to be done on the design and execution of Big Philanthropy, and it would be good to imagine a sector being proactive in the conversation.