“Be Vigilant.” Immigration Funders Look Toward 2021 with Cautious Optimism

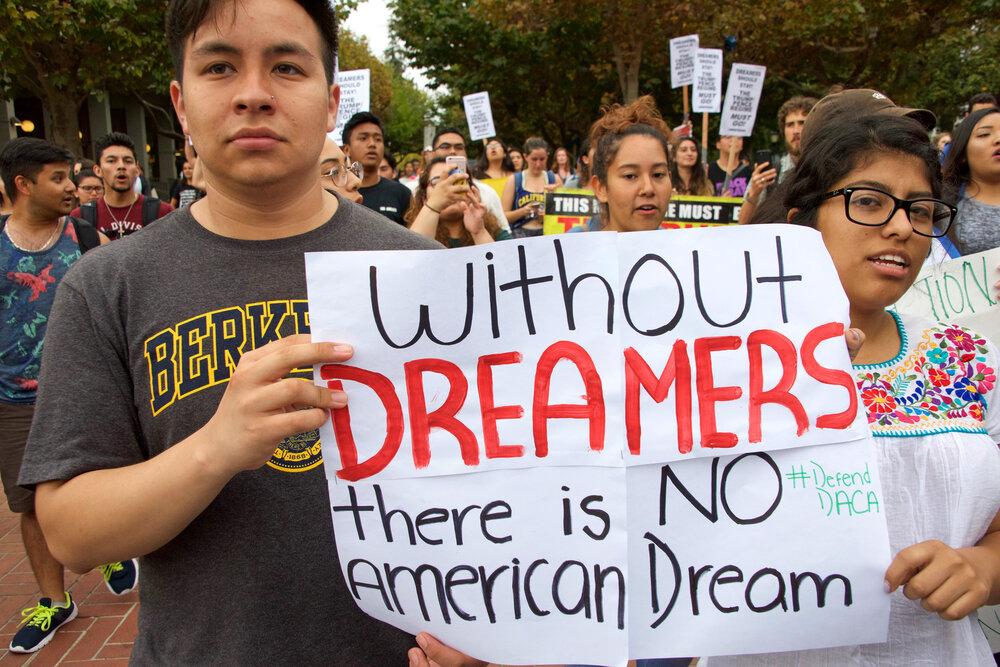

/Photo: Sheila Fitzgerald/shutterstock

Four years ago, the election of Donald Trump left immigrant justice organizations and their funders reeling. Winning the White House after a campaign full of stark anti-immigrant rhetoric, the then-President-elect promised to remake U.S. policy along xenophobic lines. And Trump did just that with a flurry of executive actions during his first 100 days that continued throughout his term. Those actions, taken independently from Congress, gave rise to some of the most infamous practices of the Trump era, including inhumane immigrant detention and family separation at the border.

For immigrant advocates in philanthropy, Trump’s initial ascent did spur some big changes to the number of funders operating in the space. In particular, rapid-response funding got a major boost in the aftermath of 2016 as grantmakers moved to protect people and organizations made more vulnerable by the new administration’s policies. Intersectional movement building also found itself better funded as immigrant and refugee rights advocates emerged to lead the anti-Trump “resistance.”

Now, at the end of an unprecedented year and an unprecedented presidency, immigration funders once again face an uncertain future. But this time, it’s a more hopeful one. Unlike, say, criminal justice practices, immigration and refugee policy is largely a national matter, under the discretion of the executive branch. President-elect Joe Biden ran on a promise to speedily unravel Trump’s draconian immigration policies, and there’s a lot he can do early on to make good on those commitments.

At the same time, the new administration will face significant headwinds in its pursuit of that project, including an immediate need to focus on COVID-19, as well as what a recent Migration Policy Institute brief described as “a dizzying array of Trump executive actions, policy guidance and regulatory changes—some interlocking and thus difficult to unwind—atop a long-antiquated immigration system.” Redesigning that baroque system via comprehensive congressional legislation is the holy grail of immigration reform. But it’s also a highly uncertain prospect, given the possibility of a divided legislature come February, or even slim Democratic majorities.

With all that in mind, most immigration funders have spent the time since Biden’s victory in a state of guarded optimism. As Marissa Tirona, the new president of Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees (GCIR), put it, “A switch isn’t going to turn on on January 20th when everything becomes suddenly better. There’s a lot of trauma that needs to be addressed, individually, organizationally and system-wide.”

Battle-hardened

As Inside Philanthropy gathered post-election feedback from the nation’s top immigration funders, many referenced that trauma, which has been a four-year constant among grantees and the populations they serve. But several also pointed to the resilience of advocates, service providers and movement actors, and how funders and grantees have grown the field amid adversity. “The past four years have taught [us] how to advance our goals and strengthen the immigrant justice movement, even in the most hostile conditions,” said Anita Khashu, director of Four Freedoms Fund.

A collaborative fund housed at NEO Philanthropy, Four Freedoms is a key donor-organizing vehicle for the immigrant justice movement. “Due in part to FFF’s long-term investments and intensive capacity building support, grantees have had the capacity necessary to not only fight back against attacks, but grow stronger and more resilient,” Khashu said.

Cathy Cha, president of the Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund—one of FFF’s donor partners—sounded a similar note regarding the 2020 election itself. “Activists and organizers worked 24/7 to activate and engage immigrants so they would get out and vote. And they showed up,” Cha said “Thanks in part to philanthropic support, we now have a powerful network of groups working at the state and local levels to lift up the power and voice and representation of these communities.”

Khashu, Cha and other philanthropic leaders referred to the growth of intersectional justice movements—made possible in part by long-term grant support—as a trend that must continue if the Biden administration is to be held accountable to its progressive promises on immigration. Cha noted that the same holds true no matter who’s in the White House. “We can’t depend on D.C.,” she said. “There is no doubt that we have to be responsive to what is happening in Washington. But we need engaged and activated immigrant communities to defend their rights and also to hold leaders accountable for affirmative policies.”

The good news for immigrant rights advocates is that despite the fire and fury of the populist right, public sentiment has actually been swinging in favor of newcomers to the United States. Several leaders we heard from, including Khashu at Four Freedoms and Tom Perriello, executive director at Open Society-U.S., referenced surveys and polls that show pro-immigrant narratives gaining popularity, like these findings from the Pew Research Center (scroll to the bottom for the relevant section).

Taryn Higashi, executive director of Unbound Philanthropy, and Ted Wang, its U.S. program director, also noted that trend. And like almost every funder we heard from, they linked rising appreciation for immigrants to the effects of COVID-19. During the pandemic, they noted via email, “more people have begun to recognize the critical roles that immigrants and other essential workers play in keeping the country running.” Perriello made a similar point, saying, “Our grantees have done a fantastic job of shifting the narrative toward recognition that immigrants are essential to our response to COVID and to the economic recovery, too.”

Nevertheless, as Perriello and others pointed out, federal relief for American workers via the CARES Act excluded undocumented immigrants—many of whom work in essential roles—and effectively locked out many American citizens from receiving aid because they share a household with undocumented people. Because so many immigrants—undocumented or not—occupy essential roles, they’ve been disproportionately affected by the virus, contributing to disparities in COVID-19 mortality between white people and people of color.

And even though immigrants and refugees featured less in public debate around the 2020 election than in 2016, heavy-handed immigration enforcement has continued throughout the pandemic.

A pivot to Washington

So what steps are immigrant justice funders taking in the election’s immediate aftermath? According to Tirano at GCIR, as well as Daranee Petsod, former president and current senior advisor, there’s a definite element of “wait and see.” For its part, GCIR has been conducting post-election scenario planning with some of its membership, including funders associated with Delivering on the Dream, GCIR’s network of state and local funding collaboratives.

Tirano and Petsod cited the need for support to organizations defending and implementing DACA, which a federal judge recently ordered the government to reinstate. They also mentioned funder conversations around preparing for an expected migrant surge at the southern border. Finally, they reported ongoing discussion among funders about refugee resettlement, an area where Biden is expected to loosen restrictions, upping the cap from Trump’s record-low 15,000 to 125,000. “The refugee resettlement system has been decimated over the past four years, and infrastructure no longer exists,” Petsod said. GCIR does have a working group of funders interested in refugee issues, but compared to immigration policy at large, fewer grantmakers have demonstrated sustained interest.

One funder focused on refugee resettlement is OSF. According to Perriello, Open Society’s International Migration Initiative is helping develop a system to meet the incoming administration’s 125,000-refugee goal in a resilient way that cannot be easily undone by future administrations. “Over the past year, we’ve been working with our grantees to help design such a system, and we’ll work closely with them, fellow philanthropists and the government to build it,” Perriello said.

Open Society has a number of other immigration initiatives in the pipeline or already up and running. In addition to general advocacy for the assertive reforms Biden has already proposed, Perriello says OSF is pursuing specific “bold ideas” in the advocacy realm, including a proposal to restructure the Department of Homeland Security to deemphasize counter-terrorism in its immigration management and the introduction of a community sponsorship system for refugees in the U.S., modeled on the Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative.

Other proposals OSF is investigating include a new Federal Office of New Americans, and finding ways for the U.S. to step up once again on the international stage, for instance, by joining the Global Compact for Migration or leaning into the problem of global climate displacement.

Federal-level advocacy also features highly in Unbound Philanthropy’s plans. The grantmaker, whose funding is solely focused on immigration and refugee issues, views Biden’s election as a first step. “While a new administration may come into office with the best of intentions, it will take planning, advocacy and collaboration to undo Trump’s policies and begin building a 21st-century U.S. immigration system that is responsive to the country’s priorities, that is understood and supported by a majority of Americans, and that cannot be easily undone by future administrations,” Higashi and Wang stated.

Since the summer, Unbound has backed scenario planning to help advocacy groups develop their D.C. strategies for 2021. Unbound also funded a database that tracks all of the Trump administration’s immigration-related executive actions toward the goal of undoing them.

The Ford Foundation, another veteran immigrant rights funder, emphasized the need to continue resourcing immigrant-led movements, both to hold the Biden administration accountable to its promises and to address underlying economic and social challenges immigrants face. “The current administration has shown us how the significant discretion given to the executive branch in immigration can be used to entirely transform the immigration system,” said Mayra Peters-Quintero, senior program officer of Gender, Racial, and Ethnic Justice at Ford. “Many of our grantees will thus be prioritizing administrative advocacy and have developed ambitious and visionary agendas,” she said.

Peters-Quintero pointed out that federal spending on immigration enforcement, currently totaling over $19 billion a year, outstrips spending on all other federal criminal law enforcement combined. Even though the incoming administration will be friendly to pro-immigrant reforms, changing the enforcement behemoth in a judicious way won’t be easy, and it likely won’t be quick. Officials like Alejandro Mayorkas, Biden’s nominee to head the Department of Homeland Security (and, if confirmed, the first immigrant and Latino in that role), will have their work cut out for them.

It should also be noted that while Mayorkas has a positive reputation among immigrant justice advocates, the records of other Biden hires are more mixed. That reflects, in part, Biden’s emergent preference for personnel with experience in the Obama administration, which had a far-from-stellar track record among immigrant advocates.

“Be vigilant”

Even as immigration funders gear up to back D.C. advocacy, they aren’t placing all their hopes on the best intentions of the Biden administration. For some, the fight for immigrant justice goes beyond federal immigration policy. With COVID in mind, “We have an opportunity to look at immigration as an asset in the economic recovery and in building a sustainable and caring economy, and at strengthening labor protections for all workers, including immigrants,” Unbound Philanthropy’s Higashi and Wang said. They also stressed the need to look at immigration through the lens of racial justice and the national reckoning on anti-Black racism, and to seek partnerships abroad to better manage the flow of migrants and refugees.

For Peters-Quintero at Ford, this is “an exciting time” in which philanthropy can play a key support role in dramatically improving the lives of immigrants. “The pandemic has shown us how intertwined the fate of the nation is with immigrants, and continues to be testimony on why immigrant rights must be secured, advanced and protected,” she said.

Advocates expect the Biden administration to push for federal COVID relief that benefits immigrants—even undocumented ones. If that materializes, perhaps in a Congress where Democrats take the Senate, it’ll be a symbolic step toward congressional movement on actual immigration reform. That legislation is decades overdue. But while we can expect advocates to keep one eye on Congress and another on the White House, immigration funders seem determined to continue supporting the local and state-based movement groups that have carried the banner through the Trump years.

That appears to be the position of Heidi Dorow, director of immigration initiatives at Borealis Philanthropy. “Organizing, advocacy, litigation and provision of services will always be necessary to make change, no matter who leads the executive branch,” she said. “Therefore, philanthropy will always be called on to support the organizers, advocates, litigators, and social service providers to continue to push for change from the ground up.”

Asked what kinds of lessons she’s taking from the post-election period of four years ago, Dorow simply said, “Be vigilant.”