The Sackler Toxic Donor Saga Continues With a Ban on “Reputation-Laundering” Naming Rights

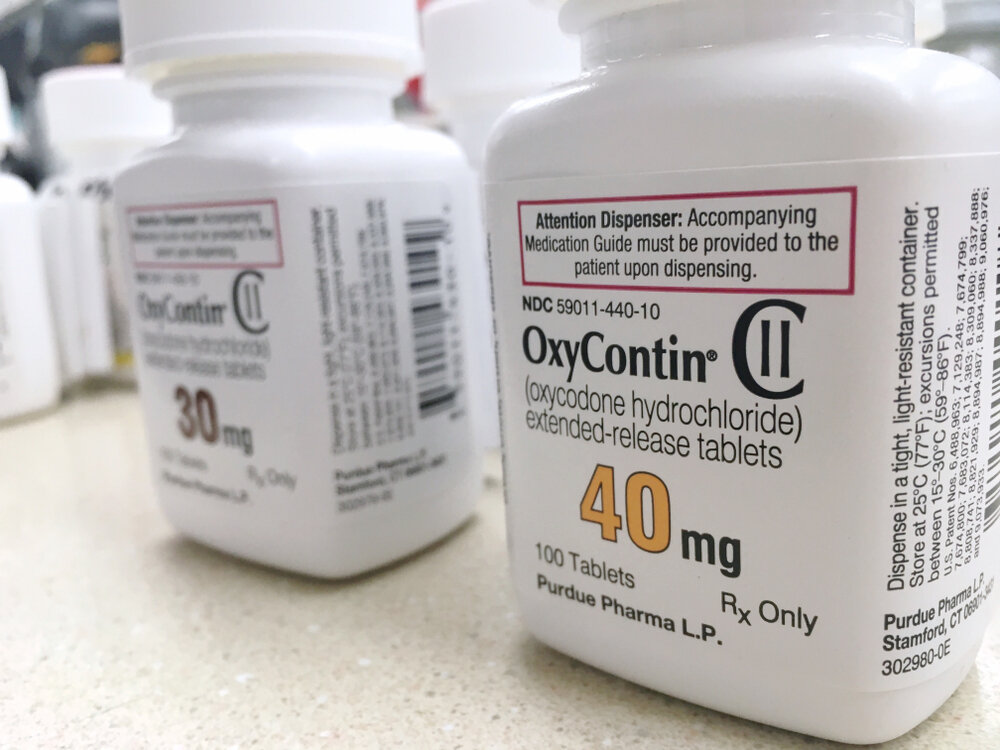

/The Sacklers made much of their money by aggressively marketing addictive opioid painkillers. Photo: PureRadiancePhoto/shutterstock

Anyone following the debate around toxic gifts will have heard of the Sackler family, whose $11 billion fortune is founded, primarily, on the sale of narcotics. Through their ownership and control of Purdue Pharma, the Sacklers have been among the biggest winners in the business of pushing legal opioids like the infamous pain medication OxyContin. Aggressive and often deceptive marketing of OxyContin and other painkillers has been a driving force behind the opioid abuse epidemic in the U.S., which has cost a half-million lives since 1999 and impacted countless more.

In recent years, the Sacklers’ chilling place in the annals of U.S. public health has blown back on their substantial philanthropic giving, as grant recipients grappled with how to escape the tarnish of the family name. Whenever the debate over so-called toxic donations comes up, the Sacklers are now often invoked in the same breath as figures like Jeffrey Epstein.

But until now, actions taken against the family’s philanthropy—separate from actions taken against their business affairs—have been limited to the realm of grantee prerogative. That is, potential grantees are refusing to touch Sackler cash, and some previous recipients are seeking ways to return it or revoke naming rights.

The latest news is a legal agreement reached between Purdue Pharma and 15 U.S. states, which has cleared the way for a $4.5 billion settlement that will resolve thousands of outstanding opioid cases. And as part of the settlement, the Sacklers will be barred from placing their name on buildings in conjunction with charitable gifts until they’ve fully paid what they owe. They’re also giving up control of two charitable foundations.

“A family that has destroyed so many lives should not be able to put its name on our trusted institutions,” said Maura Healey, attorney general of Massachusetts. “They should not be reputation-laundering while at the same time paying to abate the opioid crisis they created.”

While many will rightly wonder whether a temporary ban on naming rights is penalty enough for a clan that has plastered their name on civic spaces while profiting mightily from drug addiction, the ban is a novel step. It also raises questions about how we’ll collectively gauge and respond to donor toxicity in a time of rising condemnation of the super-rich.

Making a killing

This legal settlement is only the latest development in a saga going back decades. Many experts date the beginning of the present opioid crisis to just before the turn of the millennium, right around the time OxyContin hit the market and Richard Sackler, son of the late Raymond Sackler, became Purdue Pharma’s president.

For several years thereafter, Purdue made a killing marketing opioid painkillers to doctors across the country, who often prescribed them after receiving misleading information about their purported harmlessness. Purdue—and the Sacklers—avoided widespread scrutiny as billions in profits flowed in.

A 2007 criminal case, in which three Purdue execs pleaded guilty to misleading regulators, physicians and the public, failed to significantly harm the Sackler brand as the family kept up a generous stream of gifts to arts and higher ed institutions, often with naming rights attached.

As my colleague Mike Scutari has chronicled in detail, real discomfort around Sackler largesse only began to mount quite recently. As late as the start of 2019, only a few organizations had spoken out about the toxicity of past or potential Sackler gifts. But a rising torrent of damning information about the family’s culpability in the opioid crisis led to a domino effect as the year progressed, which saw organization after organization refuse Sackler cash.

By the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Sackler name was pretty thoroughly trashed as far as philanthropy goes—although a variety of reasons have kept many donation recipients from making a full, clean break.

Meanwhile, as these debates continued in the nonprofit world, the main drama continued—an ongoing flood of legal proceedings against Purdue and the Sacklers seeking restitution, and, in some cases, punishment.

“Getting through to the family”

This present settlement is expected to be something of a culmination of those cases, since the terms shield the company and members of the Sackler clan from any further opioid-related lawsuits. That’s a big win for the Sacklers, whose concerns about personal liability for the opioid crisis extend back to at least 2007, when one family member, David Sackler, worried about a lawsuit “getting through to the family.” That’s also when the family began pulling their wealth out of Purdue and into unrelated entities, to the tune of about $10 billion.

Fast-forward to 2019, when the lawsuit-laden Purdue filed for bankruptcy in what was no doubt a calculated move to shield it via bankruptcy protection. The current settlement is connected to those bankruptcy proceedings, and will remake Purdue into a nonprofit organization dedicated to combating the opioid crisis. As mentioned, it’ll also shield the new organization and the Sacklers from further litigation.

At the same time, the settlement mandates the release of millions of internal Purdue communications, sources that journalists and historians will be free to comb through for all time.

Patrick Radden Keefe, a journalist at the New Yorker and the author of “Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty,” detailed much of this saga in a piece in the New York Times this week. He also made a good point about that $4.5 billion—that it’s a lot of money, sure, but the Sacklers get nine years to pay it out. That puts the bill at an even half-billion a year, which the family will likely be able to cover with no great difficulty on their investment income alone, leaving their core wealth of $11 billion untouched. Penance, in the Sacklers’ case, means contenting themselves with holding onto a colossal fortune for a decade rather than seeing it grow into an even more colossal one.

Where philanthropy’s concerned, the Sacklers won’t be barred from making gifts, just from putting their name on facades. Any organization willing to overlook the toxicity factor will be welcome to Sackler cash. And as we’ve explored in the past, the Sacklers are an extended family whose various branches can be said to have differing levels of culpability in the opioid epidemic. But that’s always a matter of interpretation.

Reputation-laundering in an era of anti-billionaire sentiment

Still, the naming ban is quite a step. “This seems [like] an unprecedented incorporation of philanthropy into a legal settlement,” philanthropy scholar Benjamin Soskis pointed out in a tweet. “But just [as] significantly, it marks [an] important moment in public critique of philanthropy, highlighting that large-scale giving represents a powerful point of civic leverage.”

That’s reflected in Healey’s no-nonsense characterization of Sackler philanthropy as “reputation laundering,” in concert with a rising chorus of similar critiques. More than in the recent past, perhaps, the public sees billionaire giving as a kind of civic and moral painkiller, a kind of blood money (at least in the Sacklers’ case) paid to offset the cruelties of a system that lets such gargantuan piles accumulate—and to relieve billionaires’ personal sense of guilt.

One question going forward will be where to draw the “toxic” line. It’s pretty easy to label the Sacklers’ opioid fortune, or gifts from Jeffrey Epstein, as toxic—as a matter of good and evil, to paraphrase prominent anti-Sackler activist Nan Goldin. But what about gifts from hedge fund billionaires, or from the Facebook fortune of Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan? What about gifts—dare I say it—from the Amazon fortune of MacKenzie Scott? Coming to terms with that slippery slope is one of the crucial philosophical questions facing the nonprofit world right now.

At the same time, it could also be argued that today’s high-intensity media environment diminishes the reputational value of Sackler-style giving. Once the Sackler name was associated online with drug pushing, what good could a few museum wings or campus buildings possibly do to wash off that stain? Maybe it would have been better for the Sacklers to have refrained from all that splashy giving, avoiding the infamy they’ve gained as known and pilloried toxic donors. For one thing, Inside Philanthropy wouldn’t be writing so much about them.

I wouldn’t bet on many institutions being eager to put “Sackler” up on their facades even after this ban ends. The temptation for fundraisers will always be there, but so will the potential fallout of dealing with tainted money in a world where it’s not easy to sweep controversy under the rug.

Whether or not their tainted gifts backfired on them, it seems clear the Sacklers were playing an old-school patrician long game with their philanthropy in a world where successful reputation-laundering, if you want to call it that, requires a very different playbook.