What's It Take to Reinvent Photography In the Digital Age? Well, a Big Grant Can't Hurt

/We'll go out on a limb here and say that photography, more than any other arts medium, has been most affected by social media and the smart phone revolution.

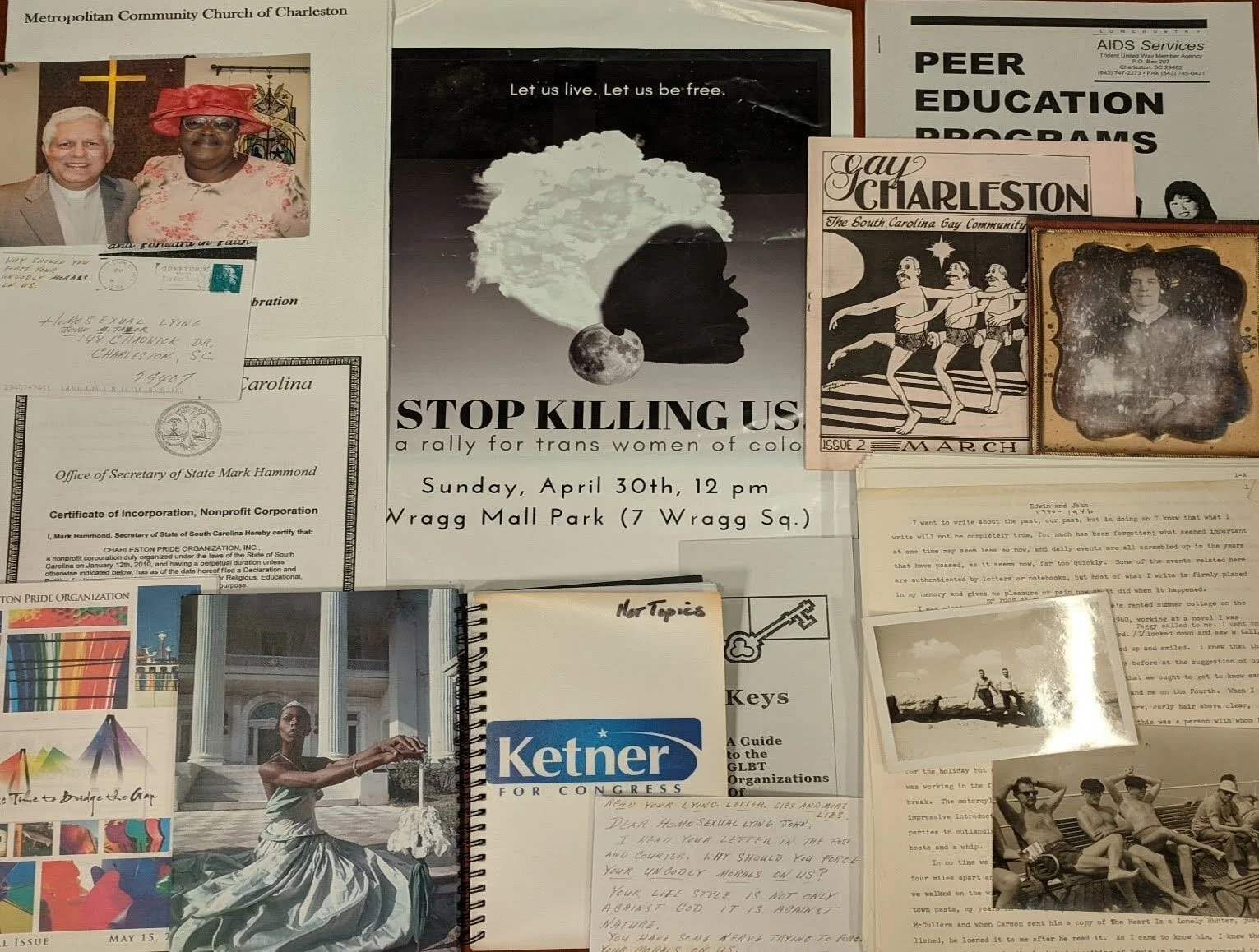

"iPhone journalism" was central to major social movements in the last 10 years, including the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street. It's empowered millions of novices who don't know the difference between shutter speed and exposure value to embrace the role of "citizen journalist." And it's consistently proven to be the most effective medium with which to shape public debate over pressing social issues in real-time.

None of this, of course, is particularly revelatory. What is newsworthy, however, is when a photography-based institution like the International Center for Photography decides to address these trends and calibrate its mission and program offerings accordingly.

The New York City-based center, which was founded 1974 as a place to collect and view images typically ignored by art museums, has some big plans in mind. First, the center is moving to a new location on the Bowery, with plans to open next year. Executive Director Mark Lubell hopes the move will boost attendance, which totals 165,000 visitors per year.

Secondly—and most importantly—the center plans to reorient its program offerings in response to the changing times. Specifically, Lubell wants to explore how the web, smartphones, and social media have revolutionized the way photographic images are distributed and consumed. It looks like he'll have some help. Equipped with a three-year, $750,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Rubell and his team will create the Center for Visual Culture, a specialized program focusing on how photographic imagery functions in our social media-saturated 21st century world.

The new visual culture center "is really going to look at some of the biggest issues of the day," Lubell told the New York Times. For instance, he noted that images have catalyzed movements like Black Lives Matter and alluded to the use of social media by ISIS. To that end, the Mellon grant will also be used to create new public programming, help the center build partnerships with other institutions, and optimally utilize its archive of photographs.

Two final points here. This Times piece, published in September of 2014, took at close look at the center's planned move to the Bowery and some of the strategic challenges it was facing. At the time, an unnamed individual within the organization noted that the board had been debating the best way to broaden the center's appeal without betraying its legacy of promoting compelling, socially informed imagery. Needless to say, it seems like the new Center for Visual Culture effectively threads the needle.

Which brings us to our second point. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation is what we call "field-agnostic." This simply means that it will happily give to any field out there—whether photography, opera, or the humanities in higher ed—as long as the recipient program aligns with Mellon's overarching goal of effectively using emerging technology to broaden exposure to the arts and catalyze discussion around timely social issues. When viewed through this lens, its gift to the center makes perfect sense.