Ten Considerations for Human Rights Funders Engaging with Social Movements in 2019

/A human rights protest in Karachi, Pakistan. Asianet-Pakistan/shutterstock

This past year was a brutal one for international human rights. As we examine the wreckage, we have no doubt we’re living through the greatest erosion of democratic culture and practice in the world in more than a generation.

Democratic institutions, civil society, independent media, human rights norms and frameworks—all are under assault amid the rise of nationalism and authoritarianism. Politicians are exploiting surging economic inequality worldwide, along with unfounded fears of “outsiders.” Making matters worse, we can no longer rely solely on the tactics that international human rights activists traditionally use to counter these forces—public campaigns organized by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), international advocacy, U.N. mechanisms and government lobbying efforts.

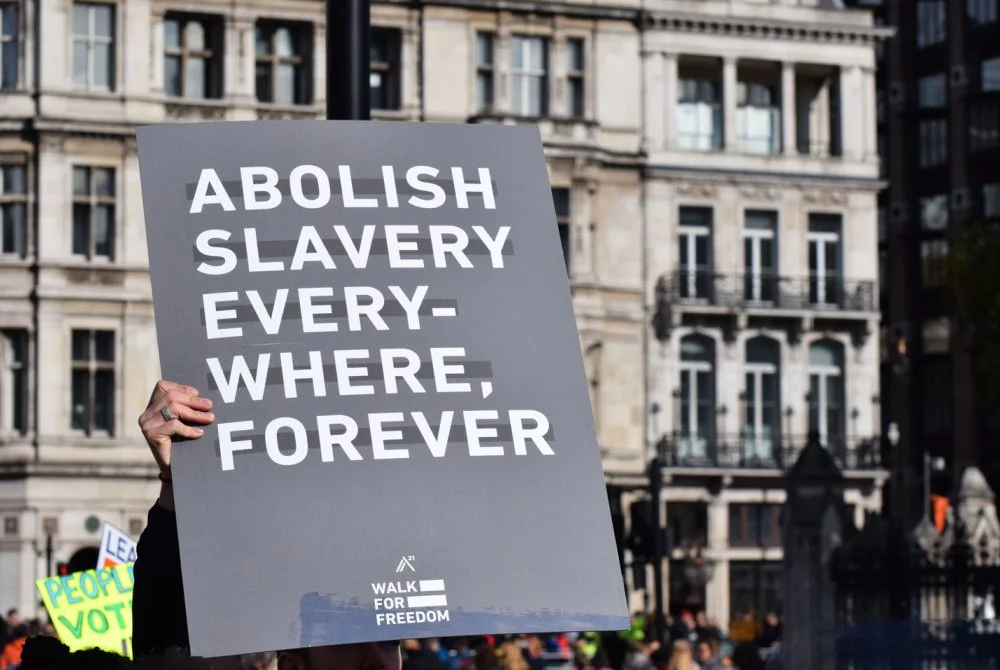

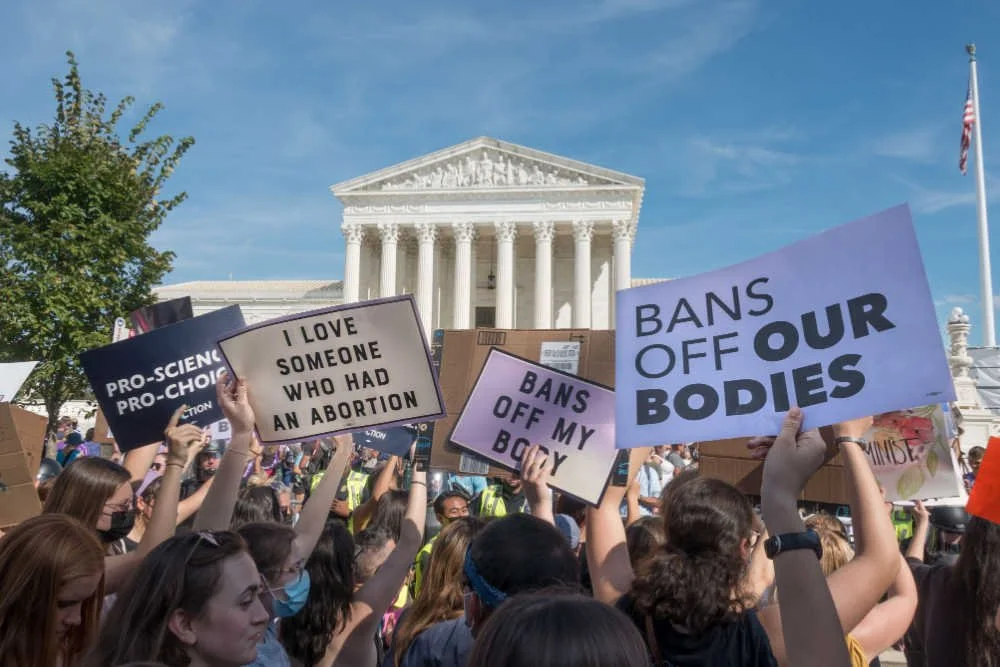

What’s the best way forward? Human rights organizations and funders are recognizing the power of social movements to offer effective resistance. Why? Among many reasons, strong social movements have built-in resilience, thanks to characteristics such as diverse membership and multiple channels for participation, that can help withstand attacks against individual NGOs and civil society organizations (CSOs). This broad, often grassroots participation generates public support and enhances legitimacy.

In times like these, supporting social movements provides philanthropy with an important opportunity to combat authoritarianism and discrimination, and to promote rights-based narratives and social change. Human rights funders are increasingly interested in supporting new narratives about the value of human rights. Strong social movements use such narratives to spur collective action and transform values. They can also advance narratives to dismantle underlying structures of social and economic inequality. Social movements are thus natural allies for human rights funders in the fight to resist anti-democratic narratives around the world.

Over more than 30 years of supporting grassroots activists and social movements in the Global South to advance social justice, American Jewish World Service (AJWS) has learned important lessons about how to provide this support in the promotion of human rights.

With more and more human rights funders interested in supporting social movements, it’s critical they understand how to be better allies with these movements. The following 10 considerations aren’t exhaustive, but they reflect our efforts to learn from social movements, as we aspire to be a better funder of social movements ourselves.

Listen and understand: It’s important to acknowledge the power dynamics between funders and social movements. Funders should listen to and respectfully engage with movements to determine their needs and priorities, including the types of financial and non-financial support they want, and whether they seek external funding at all.

Value a grassroots approach: Strong social movements are driven and sustained by grassroots mobilization. Funders that want to engage with social movements should integrate a grantmaking approach that values grassroots participation and leadership—particularly by women, youth, LGBTI people, indigenous people and other groups most affected by rights violations—in fostering social change.

Recognize that movements transcend single issues: While many funders’ grantmaking strategies are developed around a focus on a single issue, social movements sometimes push for a broad set of rights. Funders should avoid supporting movements in ways that promote the funder’s own priorities at the risk of compromising a movement’s autonomy and ability to advance interrelated social justice aims.

Provide flexible, long-term funding: Movements are dynamic entities, with strategies and approaches that change as circumstances change. As our peer funder Thousand Currents pointed out in a recent Inside Philanthropy piece, movement-building is a long-term process. Funders can sometimes be quick to support new trends, but they should consider providing long-term, flexible core funding that gives movements greater independence and the means to pursue evolving priorities over time, including the ability to build resilience and swiftly respond when under attack.

Think beyond direct funding: While long-term, core grants to movements can support their physical and virtual infrastructure and organizing efforts, sometimes, direct funding can cause more harm than good by corrupting or dividing movements, weakening their political nature, or making them vulnerable to accusations of being foreign agents. Direct funding for core work may also not be a movement’s primary need. Consider indirect forms of support, such as funding for research that supports the movement’s agenda; engaging in advocacy aligned with movement policy priorities; funding legal defense for criminalized movement activists; supporting self-care and wellness for advocates; covering the costs of activists to attend trainings and convenings, or participate in regional and international advocacy. Funders should also be willing to support the economic sustenance of activists. Movements cannot function if activists cannot afford to feed and house themselves and their families.

Fund movement-support organizations: Another alternative to direct funding of movements is to make grants to in-country movement-support organizations that specialize in helping them strengthen their skills, approaches and infrastructure. These kinds of organizations often better understand the specific dynamics, needs and contexts of local movements, and can thus better provide flexible and responsive funding. In addition, they are usually registered organizations that have the ability to receive and report on donor funding, which can help insulate social movements from some of the risks related to direct funding.

Adapt grantmaking practices: Most funders are structured to support formal CSOs and NGOs, but they should consider funding unregistered groups. While unregistered groups often play important roles within a movement, they may not have the structures in place or meet other funder requirements to receive funding, such as a board of directors, registration certificate, audited financial reports, or staff dedicated to monitoring and reporting on progress. In fact, many informal groups within movements intentionally decide not to register as an act of resistance itself, or to avoid surveillance, oversight and criminalization by governments. While options include providing indirect support to such informal actors or channeling funding to them through movement-support organizations, funders might also consider relaxing or adjusting their funding and reporting requirements to fund these groups directly.

Support collective and holistic security: Funders typically provide safety and security funding to individual activists or formalized organizations. However, movements experience different sorts of threats and risks based on their collective nature. Funders can alleviate these threats and strengthen the resiliency of movements by funding more holistic and collective forms of safety and security, such as wellness and self-care for movement activists.

Foster solidarity and movement-building: In an increasingly challenging political environment, it’s critical for movements to have resources to build alliances across constituencies and sectors, such as indigenous, peasant and women’s groups, organized labor, journalists and independent media, and activists across national borders. Funders can support movement-building by providing resources for movement activists and allies to come together to share knowledge and develop strategies for advancing common aims.

Redefine impact: Human rights funders often define success by the achievement of a policy change in a certain time period. Movements, on the other hand, usually aim to create social change that transcends such measures. For instance, social movements might also work to generate public support to ensure that new policies and laws they advocate for take effect. Also, the very process of building collective action through movements creates stronger, more engaged civil societies and citizens better able to create sustained social change. Funders should rethink what “success” or “impact” means to reflect the wider aims of social movements. The success of conservative funders in supporting the rise of right-wing movements in the U.S. should also challenge us to think about measuring change in longer horizons, perhaps even 10 to 20 years.

Increased funder support for social movements alone is not going to magically turn the tide for the many struggles that engage human rights activists and organizations today. Still, more effective funder support, together with greater recognition for the important role that social movements play in advancing social justice, is a step in the right direction.

In 2019, let’s pledge to develop more honest reflection and learning within our human rights philanthropic community about what is and isn’t working as we support social movements. We should seek to work jointly on strategy and engaging in dialogue with other funders and with movements. To defend the values that we believe in, we must all—funders, social movements and human rights organizations alike—work together better in 2019.

Payal Patel and Jonathan Hulland are senior program officers in the Land, Water and Climate Justice program of American Jewish World Service, which supports more than 450 human rights groups in 19 countries